At Massachusetts General Hospital, and across the globe, X-ray imaging is regarded as an eminently useful and fully established technology. There was a time, though, when it was not only novel but indeed revolutionary, and even kind of terrifying. Prior to the introduction of the X-ray in the final days of 1895, seeing inside the body without any kind of surgical intervention was pretty much an unthinkable proposition. So the revelation that we now could — and relatively easily at that — upended assumptions about how the world works, and subsequently set people to exploring this new way of seeing.

In this series, we explore the different ways people in Boston and surrounding areas reacted to the discovery, as described in contemporaneous newspaper reports as well as in other sources. As we will see, their responses weren’t always as measured as one might expect. It wasn’t long before the hullabaloo over the new type of light led to the introduction of X-ray imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital — and eventually to the establishment of the Mass General Department of Radiology.

January

On January 7, 1896, two months after German physicist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered the X-ray and 10 days after he published his findings, the Boston Evening Transcript ran a story on its front page with the tantalizing headline: “A New Light Discovered.” A special dispatch from the New York Sun, the article announced that “Professor Routgen [sic] of the Wurzburg University has discovered a light which, for the purposes of photography, will penetrate wood, flesh and most other organic substances.” It went on to describe examples of each of these and, importantly, briefly outline the process by which Röntgen obtained the images.

A translation of Röntgen’s paper wouldn’t appear in the U.S. until it was published in the January 31 issue of the journal Science, but the newspapers’ descriptions of the work were enough to spur others into action. Physicists had already been exploring the properties of electricity in the presence of a vacuum, so they already understood the fundamentals of the phenomena underlying the X-ray. In many cases, all they needed to generate the rays themselves was a brief account of Röntgen’s specific insights about the phenomena.

By no means, though, were physicists the only ones roused by the new discovery. Reporters were also quick to recognize the import of the X-ray. An article in the January 18 issue of the Boston Evening Transcript introduced the X-ray as “the newest and one of the most astounding marvels of the advance of scientific discovery” and went on to demonstrate the twin emotions of exhilaration and fear that would animate the public’s response to the news in the early months of 1896. “The results of this new process are likely to be of the utmost value in medicine and surgery,” the reporter wrote, “while one can easily imagine that in malicious hands it might be applied to mischief.”

The article also pointed to broader discussion by public intellectuals of the day, noting that the “new invisible light” was “wholly credited by men of so great authority as Edison” — referring, of course, to Thomas Alva Edison, the American inventor and businessman who in many ways helped usher in the modern, industrialized world.

“Edison says [the discovery] will put an end to vivisection,” the writer continued, “for there will be no further excuse for it. The use of radiant heat, when it shall have become manageable, will reveal the presence of diseases, and will locate without error a bullet which has entered the body. At once we remember the terrible mistake of the surgeons in the case of President Garfield, and realize that with this method the exact place of Guiteau’s ball would have been discovered at once, and Garfield’s life probably saved.”

February

Within weeks of the announcement of the X-ray, interest in the discovery had exploded both in academic corners and among the general populace.

By early February, dozens of researchers in the U.S. had succeeded in producing X-ray images. The first to publish his findings was Yale University physicist Arthur W. Wright, an accomplished investigator and the first person to receive a PhD in the sciences outside of Europe. It wasn’t long, though, before John Trowbridge, director of Harvard University’s Jefferson Physical Laboratory, was describing his own findings.

An article in the February 16 issue of the Boston Globe noted that Trowbridge had been devoting considerable time to investigating the new kind of ray. “It was about the last of January that he made his first thoroughly successful attempt with it,” the Globe reporter wrote, “and since then he has had but few failures.” The reporter had seen a half dozen or so of the resulting images, including images of the number of coins in a purse, of the bones in a chicken’s leg and foot, and of a hand photographed through an inch-thick board.

Trowbridge told the reporter, “We are now trying to photograph through thicker substances, to obtain, for example, a clear image of a bone or a solid in the thickest part of a man’s body. All that we have hitherto been able to accomplish is to obtain images through a comparatively thin body, because the cathode rays cannot be developed strongly enough at present to do much more than they are now doing.”

In addition, the article outlined efforts underway at “the institute of Technology” (that is, MIT) largely carried out by H.M. Goodwin and Charles R. Cross, who had produced images of the bones in living human hands showing, for example, broken knuckles or bones. Elsewhere in the greater Boston area, a Professor Whiting of the all-women’s Wellesley College was also exploring the X-ray — seeking to determine, for instance, the relative transparency of different substances when exposed to the ray.

The latter efforts inspired an attempted witticism in another local scientist, who exclaimed, “half jocosely,” according to the Globe reporter: “Perhaps the women at Wellesley will discover an entirely new kind of ray — a feminine ray, or something like that. Or they may find that the Röntgen ray is composed of two parts, male and female.”

The world was “agog,” as the Globe writer put it, and newspapers breathlessly reported on every development with the new kind of ray, including experiments exploring a host of potential applications. A series of headlines in the February 13 issue of the Globe cried out, for example: “Men May Soon See Themselves Think” (by imaging expansions and contractions of the brain lobes during thought processes), “Full Process of Digestion Can Now be Watched” and, sadly, “Rays Have No Power to Restore Life.”

For many, the introduction of the X-ray came with darker intimations as well: hints of nefarious uses and the perils of perhaps seeing and knowing too much. Writing in the February 10 issue of the Globe, for example, columnist and humorist Bud Brier explored some of the more troubling implications of the new technique. He proclaimed in his column: “The promise of a French savant to so adapt the ‘cathode rays’ — if they are the cathode rays — to the eyes … may be the most startling feature of all.”

Brier may have been referring to the French author and Protestant minister Charles Recolin, who in the months after Röntgen’s discovery published a short story called “Le Rayon X” [“The X-Ray”]. In the story, a physician injects one of his eyes with a serum that makes the eye susceptible to Röntgen rays and is overwhelmed by the access this gives to the secrets of the soul. Ecclesiastes was right, the physician concludes: “Whoever increases knowledge increases sorrow. God has retained the worst part for himself: the truth.”

Brier echoed the fears expressed in Recolin’s story should the X-ray ever be adapted to the human eye, though in his column he expressed decidedly more prosaic concerns: “Clothes, of course, after that would be worn simply as a protection against the cold.” (We can only assume that Victorian sensibilities prevented him from saying people would use the X-ray to see other people’s naked forms.). “Everybody could see how much money everybody else had in his pocket. Skeletons would be visible in carefully locked closets. We should begin to feel that the very secrets of our hearts were being laid bare. And even now we see rather more than is good for us.”

March

Scientists in the hallowed halls of Harvard, MIT and Wellesley weren’t the only ones exploring the wonders of the new type of photography. By March, non-experts across Boston and its environs were tinkering with the technology. An article in the March 14 issue of the Boston Evening Transcript — titled simply, “X-Rays for Everybody” — elaborated. “It may surprise some to know that more than a hundred amateurs in Boston are experimenting with the x-rays,” the article read, “this being the estimate made by a dealer in scientific apparatus who has supplied many outfits for producing the rays.”

More significant than any of these, though, were the efforts of area hospitals to translate the technology for medical use.

Even amidst the breathless coverage in the newspapers and the wonderstruck response among the populace, medical professionals were quietly probing the potential of the X-ray for a range of applications in the clinic. The first documented medical X-ray image in the U.S. was produced at Dartmouth College on February 3, less than a month after the technology arrived on American shores. The X-ray photographer was Edwin Brant Frost, a professor of astronomy at the college; the subject was a boy with a broken arm, a patient of Frost’s physician brother, G.D. Frost of Hanover.

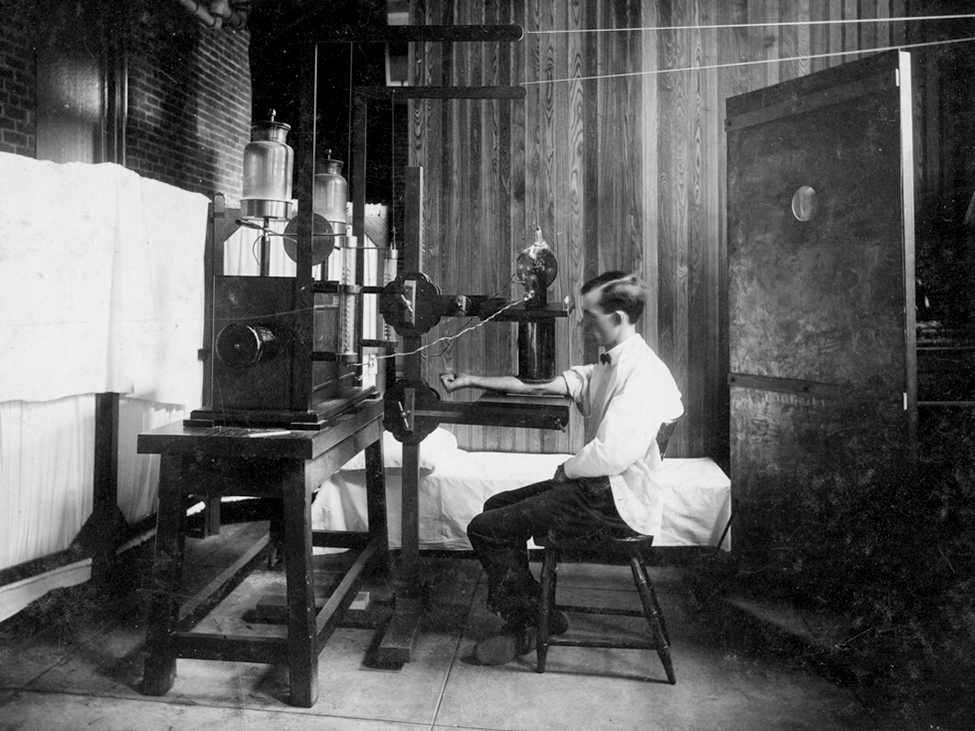

The first documented medical X-ray in Boston came shortly after. Francis H. Williams was a medical faculty member at Harvard who practiced internal medicine at Boston City Hospital in the South End. Working with Ralph Lawrence and Charles L. Norton at the Institute of Technology, he brought patients from the hospital to the institute’s physics laboratory to perform X-ray studies using apparatus assembled in the lab. He and colleagues reported the work in the February 20 issue of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal.

In May, Williams launched an X-ray facility within the hospital itself, where he and colleagues could readily image patients. By then, work with the new technology was also underway at another area hospital: Massachusetts General.

MGH was one of the oldest and most venerable hospitals in the region — even in 1896 — with a long history already of medical innovation. Half a century earlier, for example, in 1846, MGH physicians had launched a new era in medicine when they successfully demonstrated use of ether as a surgical anesthetic. When news of Röntgen’s remarkable new ray broke, the hospital recognized the clinical potential of the ray and decided to explore its possible uses. There was one problem: because the field of radiology did not yet exist, never mind a department of radiology, it wasn’t clear who in the hospital would spearhead the effort.

Fortunately, looking to capitalize on another burgeoning technology, The hospital had introduced a medical photography department only a few years before. For reasons that are not readily apparent today, responsibility for medical photography was assigned to the hospital apothecary. So, with no obvious home for X-ray otherwise, the task of developing the technology for use at MGH fell to 26-year-old Walter Dodd.

As described in a 2001 history of radiology at Mass General, Dodd was a classic “self-taught Yankee tinkerer” with an innate curiosity about the world and an easy grasp of new concepts. Born in fact in London in 1869, he was raised from the age of about 10 by his older sister and her family in Boston. When he was about 18, he began a job as a janitor at Harvard’s Boylston Chemical Laboratory. He quickly immersed himself in his new surroundings, auditing chemistry lectures, reproducing lab members’ experiments on his own and eventually enrolling in classes for credit. In 1893, he joined MGH as the assistant apothecary. The following year, after passing the necessary examination and earning his license as a pharmacist, he was promoted to apothecary.

When he was tasked with investigating the potential of the X-ray, Dodd and his assistant, Joseph Godsoe, first assembled an X-ray rig, testing various components of the rig along the way. Next, they took their apparatus to the “nerve room” in the hospital’s Gay Ward. The nerve room housed a two-plate static generator used for treatments involving electric shock stimulation.; the generator would also produce the current needed to activate the X-ray tube. It was here that Dodd and Godsoe acquired the first images with their X-ray machine. The exact date of this milestone has been lost to the mists of time, but science historians generally place it in mid-March 1896.

And so, barely two months after news of the X-ray reached the United States, still amidst a wave of public fascination with this new type of light, an apothecary and his assistant introduced X-ray imaging to Massachusetts General Hospital. Walter Dodd and Joseph Godsoe could not have known this at the time, but they had just laid the cornerstone in the foundation of what would become the Mass General Department of Radiology.

References Cited

- “A New Light Discovered.” Boston Evening Transcript, 7 Jan. 1896, p. 1.

- “Electrical Science.” Boston Evening Transcript, 18 Jan. 1896, p. 16.

- “Professor Röntgen’s Discovery.” Science, vol. 3, no. 57, 31 Jan. 1896, p. 163.

- Brier, Bud. “Under the Rose.” Boston Globe, 10 Feb. 1896, p. 3.

- “More Wonder.” Boston Globe, 13 Feb. 1896, p. 4.

- “Boston X-Ray Pictures.” Boston Globe, 16 Feb. 1896, p. 25.

- “Rare Anomolies of the Phalanges Shown by the Röntgen Process.” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, vol. CXXXIV, no. 3, 20 Feb. 1896, p. 198.

- “X-Rays for Everybody.” Boston Evening Transcript, 14 Mar. 1896, p. 20.

- Linton, Otha W. Radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital: 1896-2000. The General Hospital Corporation, 2001.

- Recolin, Charles. “The X-Ray (Le Rayon X).” The World Above the World, edited by Brian Stableford, Black Coat Press, 2011, p. 127.

Image Credits

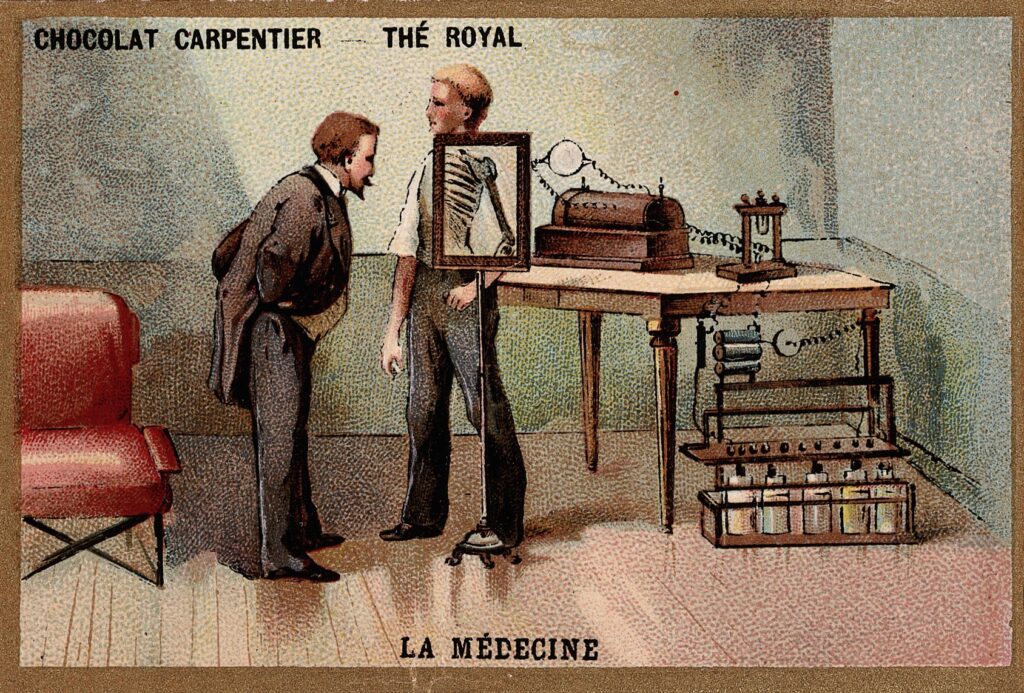

Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen looking into an X-ray screen. This file comes from Wellcome Images, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the United Kingdom. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Entrance to Harvard University in the 1890s. Public domain image available through the Library of Congress’ Public Domain Archive.