Boston and its surrounding areas were struck by a kind of X-ray fever after news of the discovery of the ray broke in early 1896. Academic researchers raced to reproduce Wilhelm Röntgen’s original findings, enthusiasts across the city built rudimentary X-ray systems with which to amaze their friends and family, newspaper columnists and others riffed on the idea of being able to see things we were never meant to see, and much more. (See “When the X-Ray Was Young, and a Little Bit Scary [Part 1]”).

One might expect the frenzy to have ebbed a bit after after the initial burst of excitement. But if contemporaneous newspaper accounts are anything to go by, the X-ray mania in Boston continued well into the summer of 1896. In Part 2 of this series, we look at the city’s still-rapt, and occasionally silly, response to the discovery in the second part of the year.

Romance a la Röntgen

By the spring of 1896, the endless stream of developments concerning the X-ray was starting to make newspapers writers giddy. “It is amusing to find that an actress has been the first woman to press the Roentgen photographic discovery into her service in the law courts,” read an April 3 article in the Globe. The article described a case in which one Miss Gladys Ffolliett tripped on an allegedly broken staircase in a theater and sued the theater for damages related to the injury to her foot — showing an X-ray image of the injury during the proceedings. “One of these days we shall have the male defendant in a breach of promise case producing a Roentgen photograph to prove that he is afflicted with a marble heart and was therefore the merest creature of circumstances and not responsible for his actions in an affair in which sentiment was concerned.”

A better quip came from Thomas Edison. An article in the April 12 issue of the Boston Post took a lengthy look at new discoveries in electric lighting by Nikola Tesla and D. McFarlan Moore as well as by Edison. In an interview conducted for the article, Edison noted that he had lately been distracted from his work with lighting. “You see, when Professor Roentgen made his wonderful discovery of the X rays, I dropped everything in order to repeat the experiments here.” And as soon as word got out that he was exploring the new type of light, he was deluged with letters from people asking if he could help locate needles, bullets or other foreign substances they had somehow absorbed.

“I had no idea that the country had so many patriots with bullets in their bodies,” he added. “It seems from my mail as if every other person must have got hit with a stray bullet.”

Readers of Boston newspapers were endlessly intrigued by the X-ray. And by now, Röntgen himself had become something of a romantic folk hero. An April 6 article in the Globe, for example, described him as a “tall, handsome man with a poetic cast of countenance.” An April 4 item in the Globe, special from the New York Sun, announced Röntgen’s geographically nearest relative — Rev. Dr. J.H.C. Roentgen, pastor of the First Reformed church in Cleveland and a cousin of the scientist — allowing the newspaper’s readers to bask indirectly in the glow of his discovery. And the discovery itself was imbued with a kind of ardor. A brief item in the April 3 issue of the Globe, entitled “Romance a la Roentgen,” reported, for instance, “An Atchison woman is writing a love story in which the cathode ray plays a prominent part.”

15 Cents Is the Price of Admission

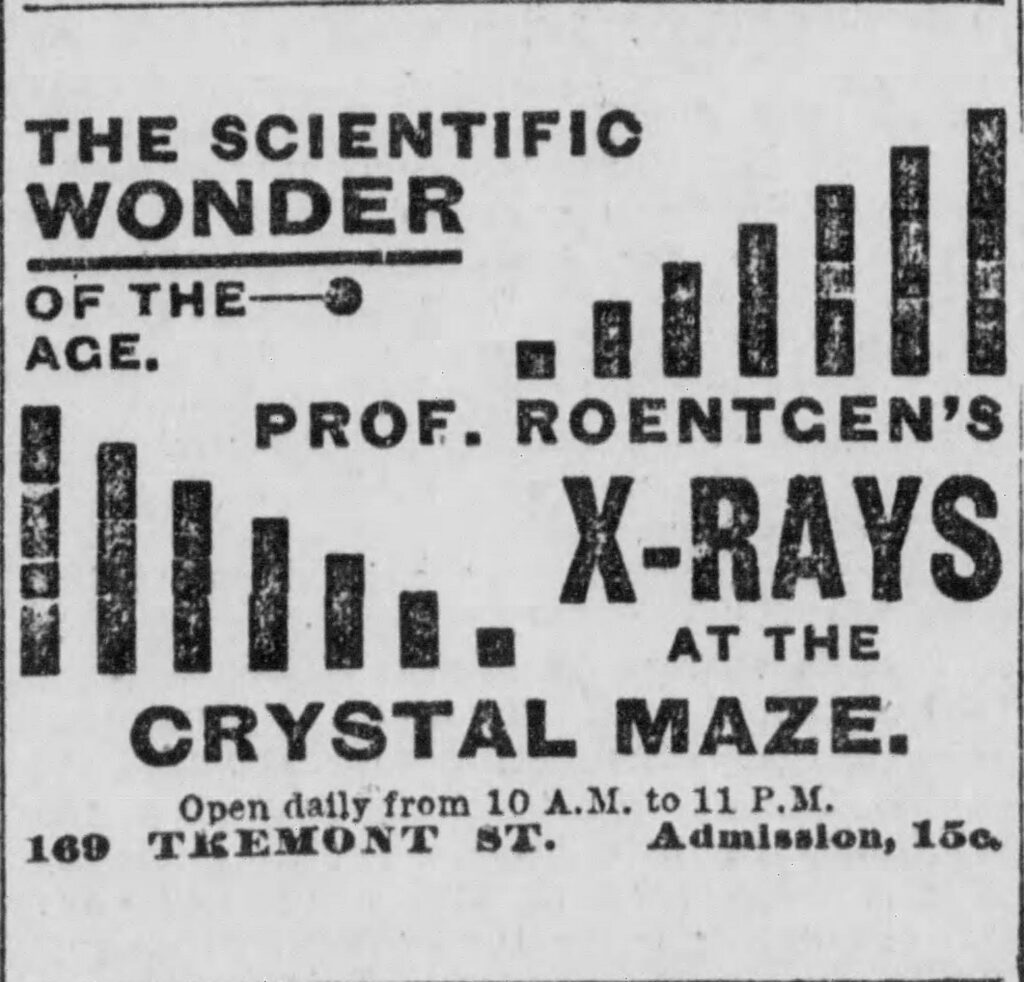

Boston residents had been reading about the X-ray for months, but few had seen it in action — only the small pockets of people who had been invited to demonstrations in academic labs and in the sitting rooms and parlors of tinkerers across the city. This changed on May 19, when the first public exhibition of X-ray apparatus (using fluoroscope attachments, thus avoiding any need for the more complicated photographic process) opened at the Crystal Maze, a popular amusement resort at 169 Tremont St. offering a hall of mirrors and other “optical illusions.” “Fifteen cents still remains the price of admission,” the Post reported, “notwithstanding this important added attraction at the Maze.”

Members of the public flocked to the exhibition, which welcomed visitors between ten in the morning and eleven at night. According to an item in the May 28 issue of the Post, many of those visitors then sought out Herr von Palm, proprietor of the Crystal Maze, and “particularly thanked him for having such an interesting apparatus.”

Still, not everyone in the city was a fan of the new way of seeing. On May 5, two weeks before the launch of the Crystal Maze attraction, a George H. Wheeler of Boston sat down and wrote a letter to the editors of the Globe raising pressing questions about the discovery. The letter, published in the paper the following day, bears reproducing in full:

“Like thousands of other readers of the ‘People’s Newspaper of New England,’ I have perused with unusual interest the marvels accomplished by the X-Ray and Roentgen Ray as reported in your columns,” Wheeler wrote. “That a man’s innermost thoughts, his conscience and the contents of his stomach, in fact, should be photographically reproduced is no doubt truly wonderful. But what I want to ask is, how has this progress of science, this getting at the true inwardness of ourselves, profited us? Has it relieved us of the torments of the undigested dinner? It will now be possible for doctors to locate a cannon ball in any portion of the human system, but are they better able to cure disease? Have all these experiments resulted in finding a remedy for our national ailment, dyspepsia, which is the foundation cause of so much suffering?”

A Most Useful Adjunct…

The occasional naysayer notwithstanding, interest in seeing the X-ray in action only continued to grow. On July 26, the Post reported “largely increased attendance” at the Crystal Maze. And there was yet more to see for the throngs of visitors. Two weeks later, on August 9, the Post described Herr von Palm’s new “enlarged and improved” attraction: a whole-body X-ray scanner. “Whereas with the old apparatus the visitor could see only the bones of the hand, or a hidden coin beneath several blocks of wood,” the article read, “now, in addition to these, can be seen the skeleton of the entire body, including the pulsations of the heart, and the coursing of the bluest blood that ever ran in Boston.”

The X-ray attraction at the Crystal Maze wasn’t simply an amusement for the masses. It was a potent demonstration of the “wonderful possibilities and remarkable power of this greatest discovery of modern times.” So even the bluest of bluebloods in Boston may have been disappointed to learn, in the same, August 9 article, that Herr von Palm would soon “remove his Crystal Maze and X rays to the West.” From the perspective of a century and a quarter in the future, the news reads as a symbolic end to the X-ray fever that swept across the city for the better part of a year.

This is not to say, of course, that the X-ray faded from view after the Crystal Maze closed. Rather, the technology enabled by Röntgen’s discovery was transitioning to a new, more mature stage of its existence. This new stage would include development and application of X-ray imaging for a variety of purposes in medicine.

In the first half of the year, even as academics and other enthusiasts across Boston were exploring the possibilities of the X-ray, and reporters were competing to describe the wonders of the technology in as lofty terms as possible, the city’s hospitals were quietly working to implement X-ray imaging as a new tool in providing care. By mid- to late summer, they were seeing positive results.

On August 6, three days before the Post shared the news of the Crystal Maze shuttering its doors, and seven months after the first reports in the U.S. of Röntgen’s discovery, an article in the Globe announced that X-Ray photography had been “found of service” in Boston hospitals. While some of the more enthusiastic predictions of the possibilities of the X-ray had yet to be realized, the article noted, the technology had “at least proved itself a most useful adjunct in the practice of surgery.”

“At the Massachusetts general hospital,” the writer continued, it what appears to be the first published report of X-ray imaging at the hospital, “not a day passes without the application of the new photography to surgical cases, its chief use being as an aid in the location of foreign substances in the body.”

A later item, in the October 24 issue of the Boston Globe, highlighted a particularly intriguing case at Mass General. The case involved one Cornelius Mack, a private at the Watertown arsenal. Mack, the Globe reported, had been wounded several years before when someone in San Francisco shot him with a pistol. Doctors never located the pistol ball. (Edison apparently wasn’t wrong about the number of people in the U.S. walking around with bullets in their bodies.) So, when Mack learned that Nikola Tesla was helping others in similar predicaments using his X-ray apparatus, he traveled to New York City to enlist the inventor’s help.

With the help of Röntgen’s rays, Tesla identified the ball under Mack’s left shoulder blade and marked the location on his skin. Back in Boston, Mack entered Massachusetts general hospital, where surgeons successfully extracted the ball from directly under the spot that Tesla had marked.

The story underscored the potential of the new technology to improve patients’ health and quality of life, both generally and in the specific case of a man who had previously had to endure the lingering effects of an old wound with no hope of relief. The final line of the article drove the point home. “Private Mack has returned to his duties at the Watertown arsenal,” it read, “feeling in better health than he has enjoyed for years.”

References Cited

- Brier, Bud. “Under the Rose.” The Boston Globe, 6 Apr. 1896, p. 3.

- Chrisman, Francis Leon. “Cheap as Daylight.” The Boston Post, 12 Apr. 1896, p. 4.

- “Herr von Palm Has Been Not a Little Perplexed of Late.” The Boston Post, 28 May 1896, p. 5.

- “Recent Discoveries Call Forth a Pertinent Question.” The Boston Globe, 6 May 1896, p. 5.

- “Roentgen Rays Locate Bullet in Body of Cornelius Mack of Watertown.” The Boston Globe, 24 Oct. 1896, p. 5.

- “Roentgen’s American Cousin.” The Boston Globe, 4 Apr. 1896, p. 9.

- “Romance a La Roentgen.” The Boston Globe, 3 Apr. 1896, p. 7.

- “X-Ray Photography Has Been Found of Service.” The Boston Globe, 6 Aug. 1896, p. 8.

- “X Rays and Crystal Maze.” The Boston Globe, 26 July 1896, p. 10.

- “X Rays at the Crystal Maze.” The Boston Post, 9 Aug. 1896, p. 11.

- “X-Rays in Court.” The Boston Globe, 3 Apr. 1896, p. 7.

- “X-Rays May Be Seen Today.” The Boston Globe, 19 May 1896, p. 3.